This was billed by most as a one-sided affair for valid reasons. Although Kei Nishikori was to play his first match in a Major – due to injuries – since Wimbledon of last year, he has lately shown signs of elevating his level of play, reaching the final in Monte-Carlo and the quarterfinal in Rome. Squeezed in between those, was a retirement in the first round in Barcelona, after going down a set vs. Guillermo Garcia-Lopez, citing a wrist injury resulting from fatigue from the previous week in Monte-Carlo. He did suffer two losses to Novak Djokovic in Madrid and Rome, so it is hard to claim that he has returned to the high form that marked his top-5 ranking back in 2015.

Facing him, nevertheless, was the wild-card recipient Maxime Janvier – ranked 304 – who had yet to play a main-draw match at the ATP events or in the Majors. He had mostly been playing Challengers, with one title under his belt (Casablanca, 2016).

The final score was an expected straight-set victory for Kei, but an unexpectedly tedious one. The Japanese player quickly admitted after the match that it was a hard-fought battle and that he felt “lucky to finish in three sets.” That was because Janvier had a plan for this match, and it was one that fit his long-term goals perfectly (more on that shortly).

Nishikori began the match serving, and Janvier began unloading. He would look to move well inside the baseline and go for direct winners whenever he could on returns. On Nishikori’s first serves that came into his strike zone, he would nail the ball, and if Kei’s serve was well placed, he would get the return back deep and accelerate on the second shot. On second-serve returns, there would be no hesitation at all. He would attempt winners on most, if not all, of them.

This plan was naturally going to also result in more errors, but that was understood. He would control the points and decide his own fate. Janvier confirmed himself after the match that it was precisely his plan because he and his coach had decided that, in general, if he were going to be successful later in his career, he needed to find “regularity in his aggressiveness.” In other words, his goal is to put out this high-octane shot production more consistently: “I’d like my game to pay off one day. I’m very aggressive, and I’m proud because I’m doing my job.”

In his first ever ATP-level main draw match, he came up just short of that goal, and under the parameters of this match, it is understandable. But he made life very hard for Nishikori for 2 hours and 19 minutes. He relentlessly put Kei on the run from the beginning of rallies. He did not stop either when he erred. For example, at 1-2 and serving, he made a forehand unforced error, then a backhand one, to go down 15-30. You would think that a player with zero experience at this level may get apprehensive and play more conservatively. Not Monsieur Janvier. He attacked again with his forehand to get to 30-30, served and volleyed successfully to go up 40-30, and held serve in the next point.

His big chance came in the fifth game. He hit two winners on the way earning three break points at 0-40 on Nishikori’s serve. Yet, as noted above, this type of tactic also carries its hazards. They appear in the form of errors. First break point was eradicated when he missed winner attempt on the return. Then, came a drop-shot attempt in the net. Finally, another forehand return in the net, and just like that, it was back to deuce.

He got a fourth opportunity to break when Nishikori, under pressure again, missed a passing shot at deuce. Maxime had a look at a backhand down-the-line winner and sailed it deep. Kei, feeling some high heat on his second serves, double-faulted to give the Frenchman a fifth chance to break. Nishikori came up with a sharp, wide serve to level at deuce again. There would not be a sixth opportunity.

Five of those for Janvier, four squandered on his errors…

First game-point opportunity for Kei, he held…

That is how it goes when you have two players on the extreme ends of the experience barometer. One with 70 wins and a final to his name in the Majors, the other with the number zero in the “matches played” column in those categories…

In fact, Janvier would end up 0/10 on break -point opportunities for the match.

In fairness to him, he played those break points in the same way that helped him reach them. His awareness of that fact manifested itself in his post-match press conference. He affirmed that he had no regrets and that he needed to press on. He understands that it may not work out for him at the end. Again, he reiterated that in the long term, this is what he needed to improve; the ability to attack consistently. He has a point. Tennis skills are not texts to be studied. You must actually learn by doing, stumble a few times, get better at it, before finally – and hopefully – reaching a higher plateau of success.

To Janvier’s credit, there were also cases where that vision worked to his advantage. At 3-4 down and serving, Janvier faced three break points himself at 0-40. Guess how he saved them? A backhand winner at 0-40, a well-hit wide serve that forced a stretched Nishikori to miss the return at 15-40, and a forehand inside-out winner completing a 1-2 punch at 30-40. He also closed the game at ad-in with a volley winner after serving and volleying.

Three errors at 0-40 up on his opponent’s serve earlier, three winners at 0-40 down on his own serve later. You win some, you lose some, and that is how you learn.

It’s too bad that Janvier was on the losing end of an easy put-away opportunity on his forehand at 5-5, 30-30, on Nishikori’s serve. That cost him a crucial break-point opportunity to go up 6-5 and serve for the set.

It’s also too bad for Maxime that the tiebreak turned into a disaster. He lost it 7-0, losing six out of seven points on his backhand errors, four of them unforced. He finished the set with 19 unforced errors**, 12 of them on the backhand. Meanwhile Nishikori committed only four errors, two on each side.

**Disclaimer on my unforced error numbers: After observing five days of qualifying matches, and few matches earlier today, and seeing the way the stat people judge and record the unforced errors, I have decided to keep my own count of them for my match analyses. An easy passing shot missed from the middle of the court is counted as an unforced error. A shot where the player’s feet are set, yet simply missed, counts as an unforced error in my book even if they are three or four meters behind the baseline. A second-serve return where the player misses it going for a winner, because they were able to balance their body to go for one, also counts as an unforced error, even if the serve had a kick on it. In general terms, if the player misses a shot that they should make the large majority of the time, that is an unforced error in my book.

Another key moment came in the beginning of the second set. You could tell by Nishikori’s body language, when he won the last point of the first set, that a deep relief had invaded him. He came out liberated to return Janvier’s serve in the first game of the second set. You could also tell that he made a decision: he was going to start taking some risks of his own on returns and not let Janvier push him around on the second shot, like he had done in the first set.

When I asked Nishikori after the match if the shift to more aggressive returns at that point in the match was a “conscious decision” on his part, he confirmed it: “Yeah, well, that was the most toughest part. I was struggling. First set I wasn’t returning well, and I tried to be little more aggressive, stepping in, and change my position.”

It worked. He hit two direct forehand return winners to go up 15-40 and finished the game on a backhand one at 30-40. It also helped that Janvier hit only two first serves out of the six total points played in that game (the Frenchman was 0/4 on second-serve points). That was all that Nishikori needed to wrap up the second set. He carried that single break all the way to 6-4.

It was, nevertheless, another high-quality set played by the Frenchman, despite not taking advantage of the only two break-point opportunities he had. Yet, the problem was not his errors this time (he only made a total of nine in this set). Nishikori stepped up on his returns for one game and got sufficient leverage with that break to pocket the two-set lead.

Down two sets, Janvier would still not fade away. In fact, at 3-2 up and Nishikori serving, he put himself in a position once again to get a decisive break. He had three different looks at break-point opportunities. Nishikori got the upper hand in the rally on the first one and saved it with a forehand winner. On the second one, Janvier went for a rocket backhand down-the-line and missed it in the net.

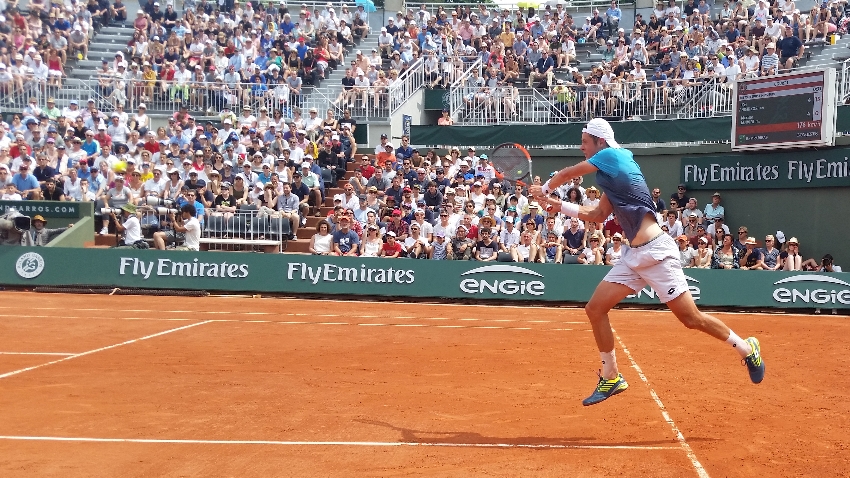

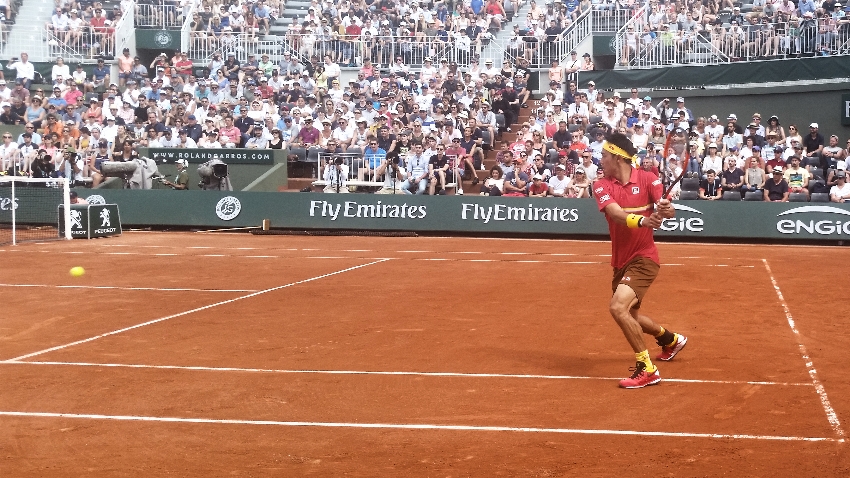

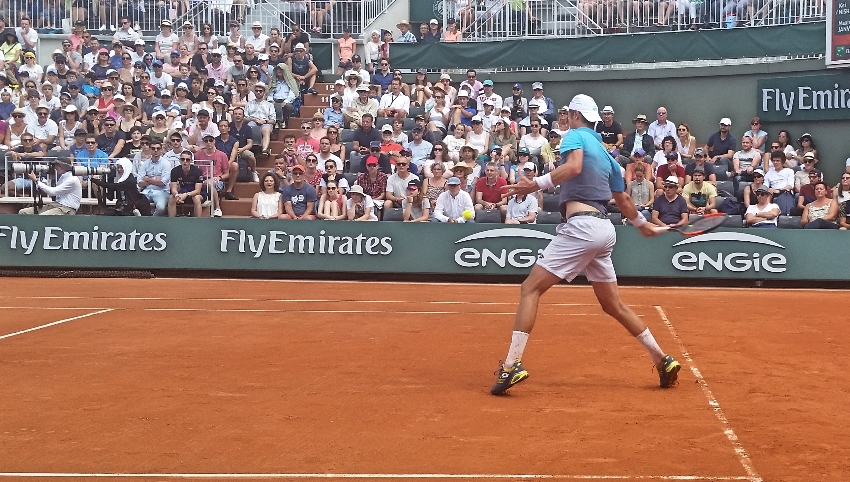

On the third, he actually had a clean look at a winner, inside the court, on a sitter. He had produced numerous winners with that same attempt, up to that point in the match. He lined up (see the photo below) and swung at it.

He framed it! The ball did not even land in the court!

When asked about that miss, Janvier said that he started that point with the same type of aggressive return that got him to the break-point opportunity – it’s true, Janvier’s return was phenomenal and Nishikori struggled to get those back throughout the match. But Kei was able to return that one in the court. Janvier praised Nishikori for making him come up with the big shots on important points and even said at one point that he wants to be consistent at a high level like him: “For me, I would like to be like Nishikori, of course.”

With that miss, disappeared Janvier’s last chance to extend the match. Nishikori held serve first, then broke Janvier’s serve to go up a break. Janvier must have framed at least four more shots in the last three games, but it was influenced by deception rather than a loss of concentration. He did not stop fighting until the last point.

Janvier ended up with 39 unforced errors to Nishikori’s 14. Kei did not play his best by any means and will need to raise his level to continue further. He also struggled with Janvier’s serves throughout the match, although that may have had more to do with Maxime’s ability to produce a wide variety of serves to keep him off balance.

In any case, what matters for Nishikori the most is that this match was precisely the type of first-round encounter that a player of his caliber needed. He was challenged by an eager adversary against whom his experience ultimately made the difference. On the road to accomplishing that, he kept his game at a solid level, without any substantial ebbs and flows to his performance.

Kei’s mental state also appears to be in a good place. When asked about how he feels about his form and fitness, he did not hesitate: “I’m feeling almost perfect. I think I had a good preparation, and I had a good couple matches before coming here. So, I’m feeling, yeah, great body-wise, and also tennis-wise, too.” He also added later that he had been “playing pretty good last couple weeks.”

His next opponent will be the winner of the match between Benoit Paire and Roberto Carballes Baena.