I have written plenty about Grigor Dimitrov before in my articles and talked about him during my guest appearances in the media and on Tennis with an Accent podcasts. I always felt – and still do – that although he has the potential to join the elites of our sport, he needed to settle on a direction for an A game plan and succeed on a specific surface before moving on to conquer all surfaces. During the 2014-16 period, he was stuck playing an ‘in-between’ game style where he would try to play consistent and outlast his opponents on slow courts, while adopting an attacking style on fast courts. Grigor’s talent level certainly permits him to play at a high level on all surfaces, using different tactics. But was it enough for him to catapult his status into the next level?

Starting with 2017, I felt that he began to indeed have a clearer vision of his target (his coaching-team changes may have had something to do with that). He seemed to have decided to take an aggressive approach in his style, which was the right move in my opinion. Because, when you make such a decision, you can begin to meticulously work on every detail of the specific pursuit without having to spread your attention on different strategies. Thus, his success in the latter portions of the 2017 campaign, culminating in his triumph at the Nitto ATP Finals in London and in a career-high number three ranking.

In 2018, another problem popped up. Having entered the year with extremely high expectations, Dimitrov had disappointing outings in the down-under swing (losing in the quarterfinals to Kyle Edmund in Melbourne and never really playing at a high level in the previous rounds), followed by more dismay in Indian Wells and Miami. I can’t evidently be 100% sure about what goes on in a player’s head but observing Grigor’s match play during February, March, and April, I am fairly certain that doubt has crept – and settled – into his mind, leading to some confidence-related damage.

The good news for Dimitrov fans is that he still believes in his game and feels that he can get back to his end-of-2017 level of play. Another good piece of news, at least from my perspective, is that he is not willing to go back to the game-searching phase of 2014-16. His match against the American Jared Donaldson is a good example of why I believe that, and his words in the post-match press conference confirm that: “I was very clear on how I wanted to play my match.” Before I unpack that statement and the rest of what he said, let me remind readers the sequence of the match to which he was referring at that moment in the press conference.

He was answering a question that touched on the last game of the third set when he was serving at 4-5, and it all fell apart for him in a matter of three points, allowing Donaldson to get the break and go up two sets to one.

Until that moment, both players were handily winning their serves. At 15-15, Grigor had a routine forehand inside the court that he had put away many times up to that point. It was a low but a short ball which allowed him to move inside the court and guide the forehand topspin to the open backhand side of Donaldson. Grigor gagged it wide and tilted his head tilted to one side in deep disappointment.

You could almost tell that doubt crept into his mind in those few seconds. In the next point, his feet seemed to get heavy (typical response by an apprehensive mind). He hit three shots off his backfoot in that rally and framed one, before finally missing in the net a sharp cross-court counter-punch forehand that had worked for him wonderfully in that set, up to that point. It was as if his elbow blew up to the size of a basketball and he could not freely swing anymore. All of a sudden, he was faced with two set points. Donaldson would only need one before Grigor would add in another unforced error, straight on the second shot after the serve.

It was a disastrous ending to an otherwise solid set on his part. He let Donaldson literally steal that third set.

Now back to more of what Grigor said pertaining to the consequences of that sequence. It had to do with him not losing his clarity despite that horrible ending to that set. He was not going to change his game plan just because of one game. For someone who has had a spring season filled with disappointments, it would be tempting to do so after making three straight unexpected errors to lose a crucial game against an underdog, and finding yourself one set away from another early exit from a Major.

Dimitrov did not fall into that trap: “I wanted to play my game the way I wanted to play my game with that margin of, you know, missing or making a winner. And I think for me that is important,” he said. It was the right decision, hats off to Grigor.

He won the fourth set in the same manner that he lost the third one, seizing on a bad sequence by Donaldson in one of the American’s serving games. Dimitrov expressed how important it was that he does not lose his game-plan clarity because of a few misses: “Okay, I missed. I missed. There’s still one set to be played and anything can happen. And it did happen, obviously, in the fourth set. I had a look. I seized that opportunity.”

In the fifth set, he found himself in the same position as he did in the third, not once, not twice, but three times, serving at 4-5, 5-6, and 6-7, to remain alive in the match. He held firm on all three occasions, hitting quality first and second serves. He was not going to let Donaldson sneak in another break, one that would have abruptly ended the match.

Then, Dimitrov had his own chance to wrap-up the Court-18 party when he broke his opponent’s serve at 7-7.

At that point, Donaldson’s physical condition was clearly diminished due to a cramping problem that reared its ugly head as early as the fourth set. It progressively got worse to the point where he could neither push off his left leg to serve nor run at 100% after balls in the extended moments of the final set.

Then, that 8-7 game made everyone ask “what?”

Donaldson went free-wheeling on his ground strokes, going for warp-speed on every shot, hitting one winner and forcing Dimitrov into three errors, to break back, out of nowhere. Grigor fans surely could not believe it. Never mind though. Their man had this, and his opponent was spent. Grigor broke serve again and finished the epic match in his next service game

It was epic and dramatically tight.

The point count ended at 176 to 170 for Dimitrov. At 8-8, it was at 169 for Donaldson, 168 for Dimitrov (Grigor won the last eight points of the match). That is how close the 4-hour-19-minute-long match was.

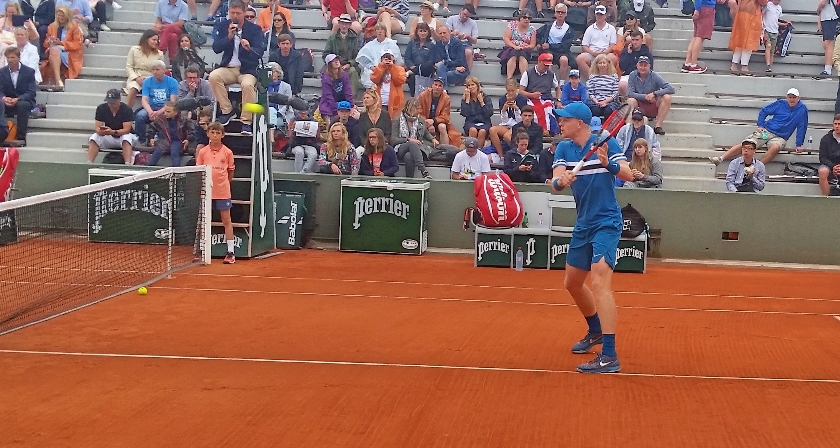

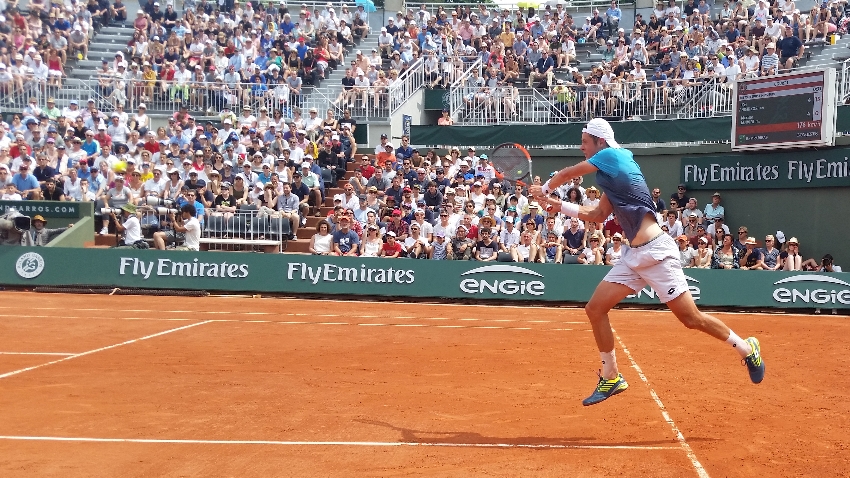

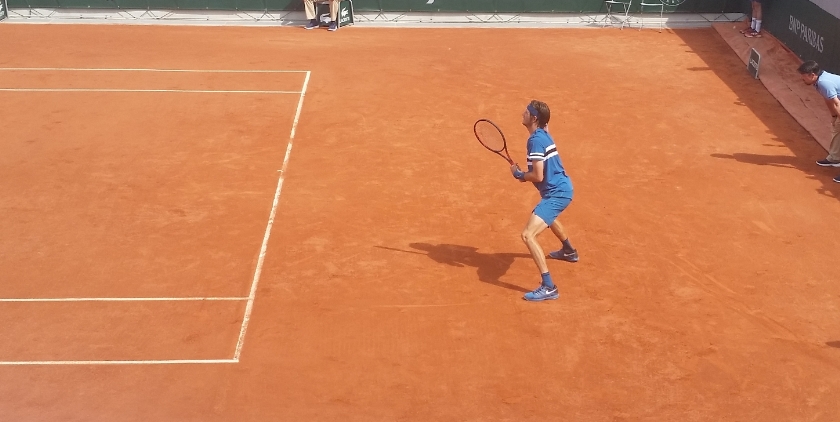

Donaldson performed at a high level for most of the match, really going after Dimitrov’s second serves on returns right off the gate. You could see a clear difference between how he prepared to return a first serve vs the second (see the photos below). Not only would he move up to the baseline to show Dimitrov his intention to attack, but he would also take two or three steps forward once the Bulgarian tossed the ball, aiming to fire the return.

It worked many times, not only to win that point in question, but to also cause havoc in Dimitrov’s mind, the next time he had to serve a second serve. If you are solely mad at Grigor for having served seven double faults in the first set, you are probably taking some credit away from Donaldson’s brilliant return tactics early in the match.

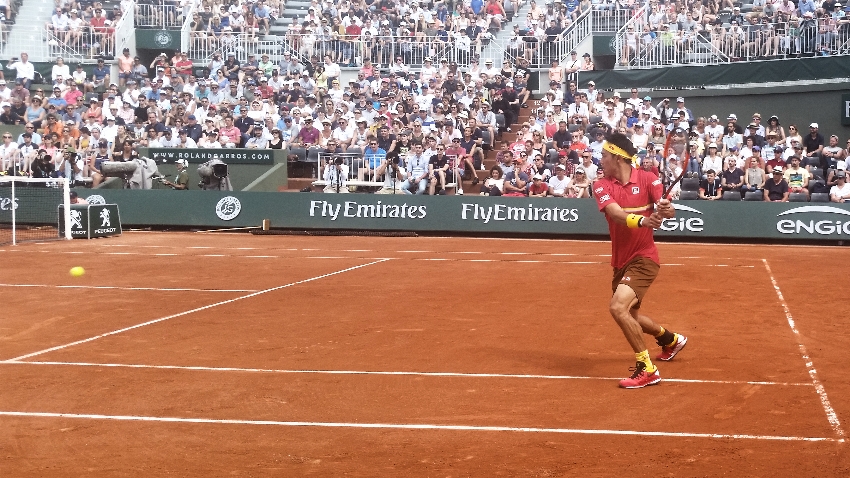

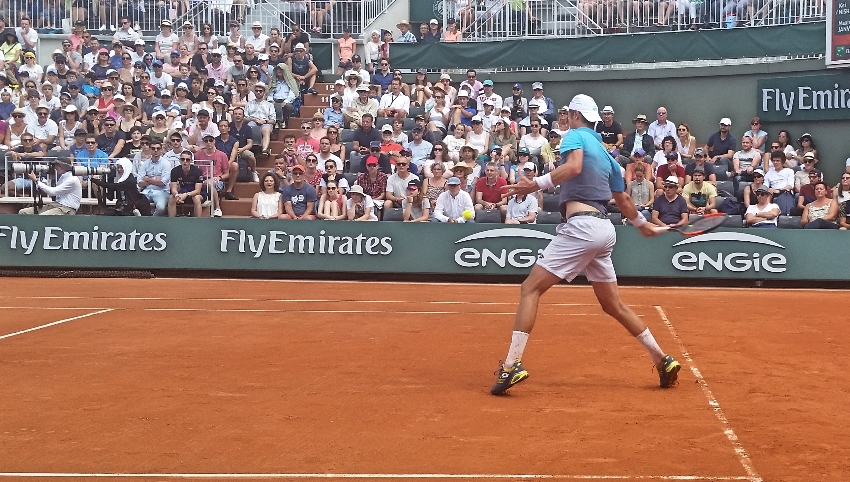

You may have also missed how effectively Dimitrov adjusted to circumvent that problem after the first set. He took pace off on some second serves (but added more spin) and he varied the target spots in the box. Donaldson was especially fond of catching the return at shoulder level on his backhand and pounding away, as in the third photo above. So, Dimitrov placed more serves in the “T” on the ad side or wide on the deuce side to make Donaldson stretch for some forehand returns (see below).

The point is, Dimitrov successfully responded to a challenge that was presented to him by a determined opponent. And that was after the catastrophic first-set tiebreaker (2-7) in which he made five errors – three of them unforced by my count**. His double fault count went from seven in the first set to a total of two for the next four sets. The positive news for Dimitrov are indeed in the details.

** In the name of avoiding repetition, see my previous Roland Garros match recaps – for example, this one – for an explanation on how I approach the unforced error count, and why I do so (I basically do my own count).

None of the above should be understood as an attempt on my part to argue that Dimitrov is in good form. I believe everyone, including Grigor himself, is aware of the fact that he has struggled not only this year, but in this particular match. The endings to the first and third sets were regrettable, and his backhand let him down at some crucial moments in the match. But it is not all full of gloom and doom as some people would have you believe, and the reason why is the central point that I tried to unpack in the above analysis.

I have mainly talked about Dimitrov, but make no mistake, Donaldson’s tactics and his performance deserve praise. I have already talked about his return plan above. He also worked Dimitrov’s backhand relentlessly, often winning the extended rallies. Don’t get me wrong. Deciding to work Grigor’s backhand is not an ingenious idea by itself. Every player is aware of his backhand being the weaker side from the baseline. What was well-planned was the way that Donaldson worked it.

He did not just feed the ball to the ad corner and make Dimitrov hit a bunch of backhands. For example, he would flatten the ball with his own backhand to Grigor’s, change pace and send one back high and deep, and add more topspin on the next shot. He would often accelerate to Grigor’s deuce corner, opening up the ad side, then hit the ball to the open ad-side on the next shot, get Dimitrov stretched to slice his backhand back, and use that opportunity to sneak up to the net and catch some of those floaters in the air for winners.

Granted, he missed some of those volleys (see the first point of the 3-2 game in the opening set), but that type of tactic is not designed for success on one or two points here and there. It is meant to make your opponent think twice every time he is stretched to hit a defensive backhand. Dimitrov did indeed miss some of those backhands, trying to keep the ball low over the net, expecting Donaldson to sneak in (see the 40-0 point at 3-3, opening point set).

For Donaldson, the match first took a downturn when, after stealing that third set on a bad game by Dimitrov, he turned around and served a dismal game of his own at 1-1 in the fourth set. He made five errors, three of them unforced, allowing Dimitrov to get ahead by a break and see the light at the end of the tunnel.

Then, when his physical condition began to deteriorate, his options for tactics got diminished (thus, the reason for which he went for rocket winners in the extended portions of the fifth set). He still fought valiantly and probably hoped for a steal – à-la third set, tenth game – in one of Dimitrov’s serving games in the late stages.

It did not happen because Dimitrov was no longer the Dimitrov of the late first or third sets. In fact, his body language in the last 30 minutes was exceptional. Being in good shape played a major role in his victory as he confirmed it himself, although not in those exact words: “when it really got down to the crucial moments, we played good tennis. But in the same time, I felt more fresh.”

Dimitrov’s next opponent is the always-dangerous Fernando Verdasco. It will be interesting to see how a high-IQ player like Dimitrov will tackle a situation in which the outcome may depend more on what version of his opponent will step on the court than what Grigor can do himself.