The well-known scenario usually repeats itself. Rafael Nadal steps on the court, Federer stands on the other side of the net. Nadal reboots the game plan which consists of two simple components. First, rip the topspin shots hard and high to Federer’s backhand over and over again. Most rallies will end with a mistake from the Swiss, or with the Spaniard stepping further and further into the court until he hits a winner. Second, hit an overwhelming majority of serves, again, to Federer’s backhand. He will chip it most of the time and miss, or will return it short, allowing Rafa to make Roger chase one shot after another for the remainder of the rally.

There are, of course, contributing factors to this plan’s success. For instance, it helps that Nadal, unlike the rest of the ATP, is not bothered by Federer’s slice backhand. It also helps that Nadal is left-handed, allowing his heavy forehand to push Federer outside the court on his backhand. It does not hurt either that Federer’s game is not based on booming flat shots, like that of some lesser players who have been able to bother Nadal. In any case, this simple plan consistently produces the desired result for Nadal, mostly explaining the skewed head-to-head record (23-11 for Nadal) between the two legends. For over a decade, Nadal has dominated Federer adhering to a game plan designed around these two major components.

In Basel, Federer showed from the first game of the match that he was determined to shake the grounds of at least one of those components: the second one. If you have watched their countless encounters, you have noticed how many times Federer chips the defensive backhand return back on Nadal’s serve. You have consequently seen how large a percentage of serves Rafa hits to the Swiss’ backhand. It happened today too. Out of 90 serves put in play by Nadal, 61 of them were directed to Federer’s backhand. That is 68% of all serves in, and that does not even include the times that Rafa served to the backhand, only to see Roger moving around the ball to hit a forehand.

At 4-2 up in the first set, after Federer had just consolidated his break, Nadal hit a first serve to Federer’s backhand, the Swiss chipped the return in the net. Another one happened at set point for Rafa in the second set. The Spaniard served to the backhand (what’s new?), Roger chipped the return, Nadal got aggressive and punished Roger. Another example was when…….

……….

No!

That was it!

Just twice!

Yes, out of the 61 times that Nadal served to Federer’s backhand, those were the only two times that Roger sliced the return back! And he lost both points.

The other 59 times, he came over the top, hitting drives! Even when he was stretched, Federer continuously refused to block/slice/chip (however one chooses to term it) his backhand returns, at the cost of making a few more errors. Federer won 6-3 5-7 6-3 to claim his 88th career title.

This… 59 times out of 61! (Image: Getty)

This… 59 times out of 61! (Image: Getty)

For example, in the first game of the match, he drove the backhand return to the corner, came in, and got passed to go down 0-1. It did not matter. Next return game, he went right back to his plan, driving more backhand returns. Did it rattle Rafa? You bet it did.

If you have access to the match, watch the 2-2 game in the first set. In the first point, he will push Rafa back (Rafa moved as if he was expecting a slice return which usually gives him time to set his feet on or inside the baseline), enough to force him into hitting a short ball, to which he will smack the winner. Four points later, at 30-30, you will see his drive backhand return, put Rafa off balance enough to the point where he will sneak in to the net, and hit the volley winner. That would end up being the game that Federer first broke Nadal’s serve, one in which he faced seven backhand returns, and came over the top of all of them! But, he was just getting started.

At the 5-3 game, he once again started with a drive backhand return that allowed him to dominate the rest of the point. Then again, on set point, the backhand drive return set up the winner on the next shot. Over and over again, Rafa expected the backhand return to fall short, have nothing more than a neutralizing pace, give him enough time to set the next shot up, and pin his opponent behind the baseline. Over and over, Roger caught him off guard.

I will give only one example out of many in the second set. At 4-3 for Federer, and 30-15 with Rafa serving, watch how Federer responds to a solid serve to his backhand with a drive that pushes Rafa deep, resulting in his miss. It looks like a bad miss on a routine shot by Nadal, but it is far from it. For a player used to receiving a weak return on that serve he just dished out, not getting the short ball you have come to expect for a decade can play tricks in your mind. Another example (out of many) took place on the second point of the 2-1 game in the final set. Rafa, finding himself in an unfamiliar spot on the second shot after the serve, missed the next shot again. On the 4-3 game, when Federer finally broke Nadal’s serve for the decisive lead, he came over the top of all the six backhand returns that he had to hit.

Did Federer also miss some of those returns? Of course he did, several times. But that is not the point. His adjustment led to Rafa to not being able to count on a major component of his Plan A that had, until today, been very reliable. Federer broke Nadal three times. He was 3 out of 7 on break points, which is, as you may suspect (unless you have not followed their rivalry), surprisingly high for Federer when he faces Nadal.

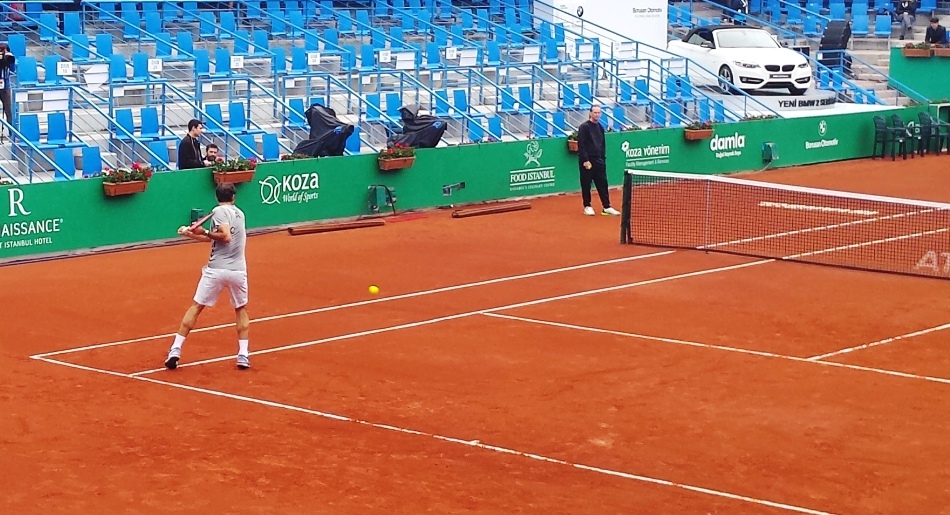

More importantly, beyond the numbers, standing tall is the pay-off for the hard work that Federer has put in since almost a year ago, meticulously honing a single skill. This pattern change did not “out of nowhere” take place on Sunday. Federer’s increased tendency to come over the top on the backhand returns since the 2015 season started in Brisbane, has been remarkable to anyone who was willing to notice it. I suspected that it was an essential goal that he set with his team, to focus on the aggressive drive backhand return, starting with the off-season practice in December of 2014. When I asked him, during the Istanbul Open, if that was the case, he confirmed that it indeed was. 2015 showed that he would apply it to his matches… Relentlessly…

Here he is, practicing it on clay (Istanbul Open)

Here he is, practicing it on clay (Istanbul Open)

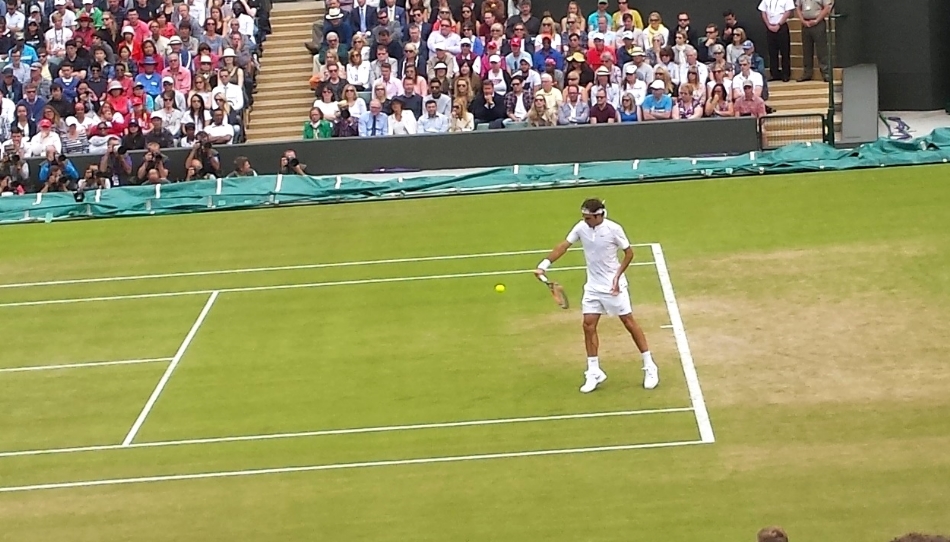

Here he is, doing it on grass, at Wimbledon (vs. Simon)

Here he is, doing it on grass, at Wimbledon (vs. Simon)

And on hard courts (Cincinnati final)

And on hard courts (Cincinnati final)

He may have had to wait ten months, but this final match in Basel was the first time that his hard work and long-term planning bore fruit, in a concrete and visible manner. The numbers showed it, his growing confidence manifested it as the match progressed, and Nadal’s reactions to the returns confirmed it. It does not necessarily mean that Federer turned the corner on his rivalry with Nadal. Let’s be honest, the conditions were favorable to Federer (indoors, hard court, Basel). It does nonetheless show that even at 33 (and 34), an elite player in the ATP, can improve a specific aspect of his game, even in the long term. Tennis is indeed a sport for all ages, with room to improve, even for the most skilled player.